College Of Arms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal

King

King

The defeat and death of Richard III at Bosworth field was a double blow for the heralds, for they lost both their patron, the King, and their benefactor, the Earl Marshal, who was also slain. The victorious Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII soon after the battle. Henry's first Parliament of 1485 passed an Act of Resumption, in which large grants of crown properties made by his two predecessors to their supporters were cancelled. Whether this act affected the status of the College's charter is debatable; however, the act did facilitate the de facto recovery of Coldharbour to the crown. Henry then granted the house to his mother

The defeat and death of Richard III at Bosworth field was a double blow for the heralds, for they lost both their patron, the King, and their benefactor, the Earl Marshal, who was also slain. The victorious Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII soon after the battle. Henry's first Parliament of 1485 passed an Act of Resumption, in which large grants of crown properties made by his two predecessors to their supporters were cancelled. Whether this act affected the status of the College's charter is debatable; however, the act did facilitate the de facto recovery of Coldharbour to the crown. Henry then granted the house to his mother  Nevertheless, the College's petitions to the King and to the

Nevertheless, the College's petitions to the King and to the

The College found a patroness in

The College found a patroness in  The reign of Mary's sister

The reign of Mary's sister

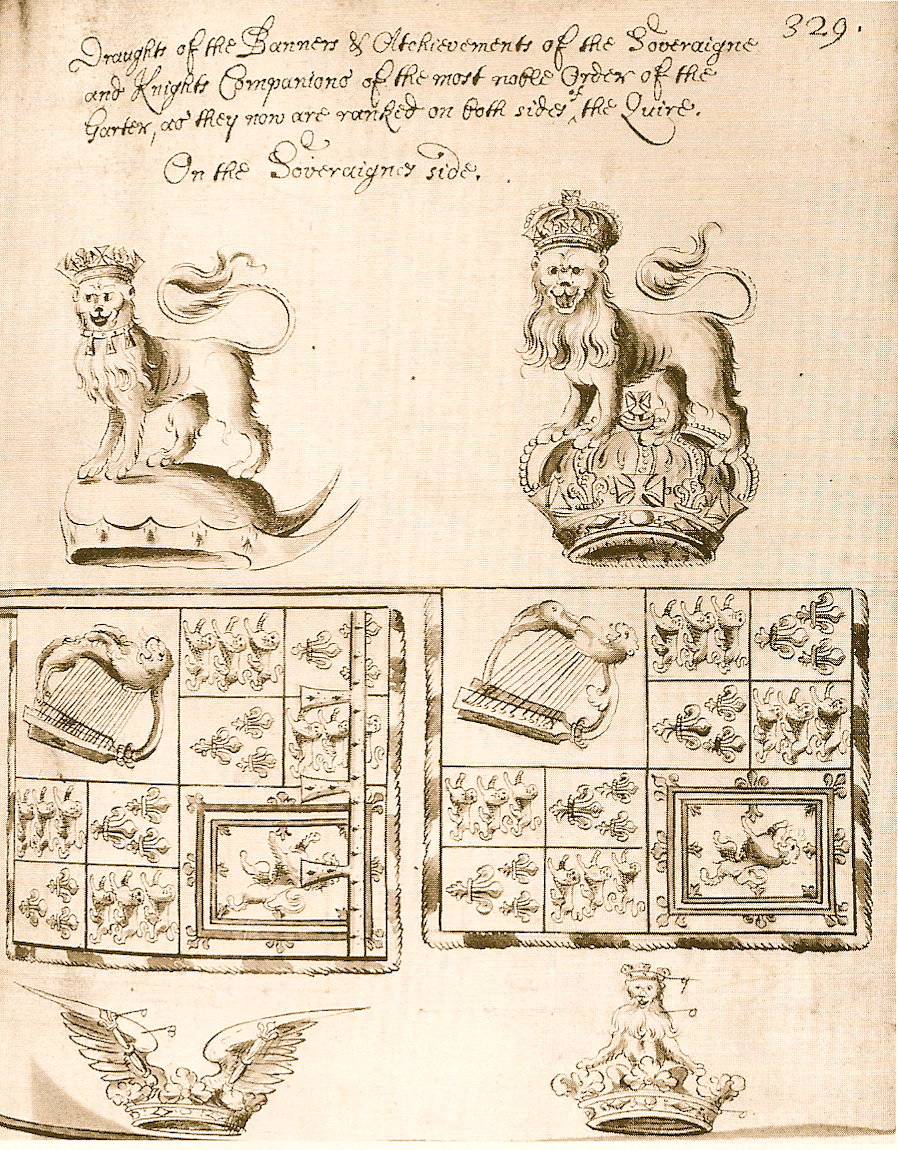

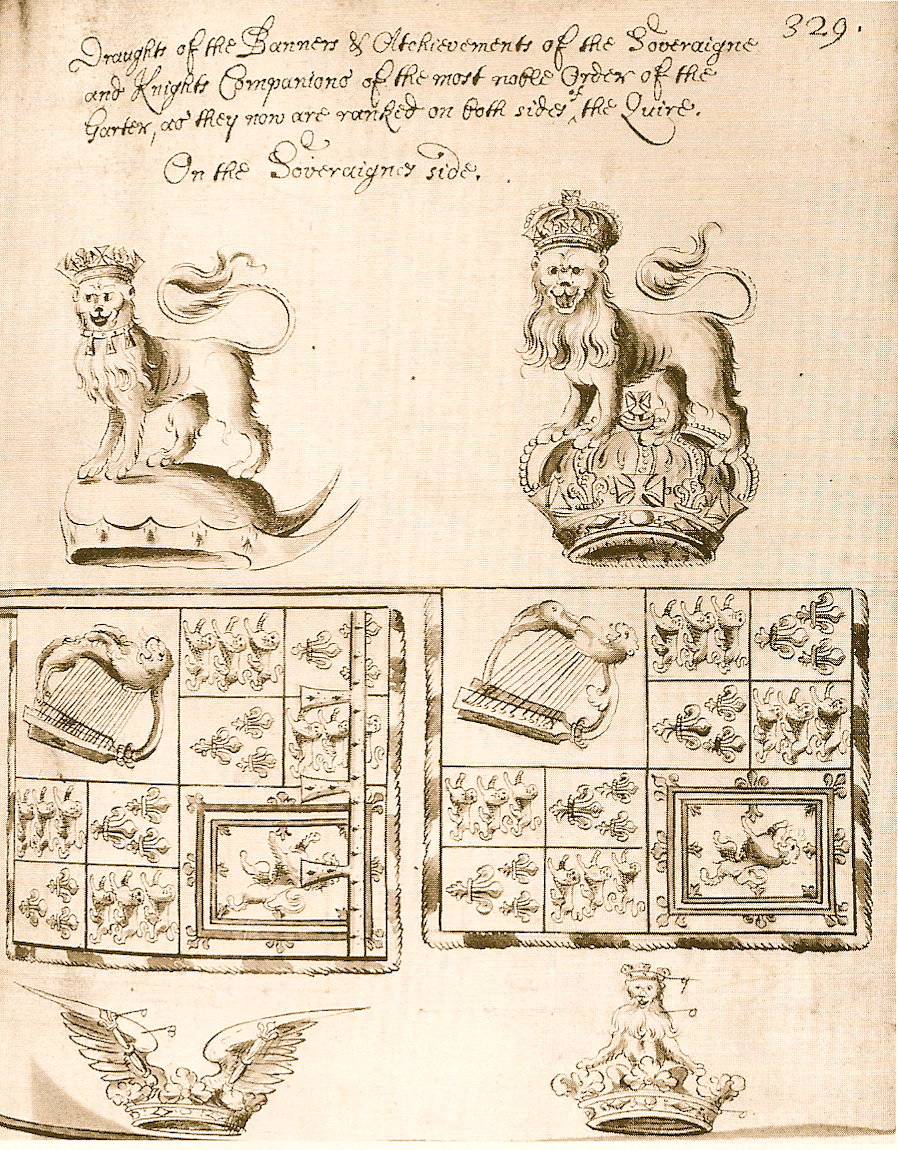

On 8 May 1660, the heralds at the command of the Convention Parliament proclaimed Charles II, King at Westminster Hall Gate. It was said that William Ryley, who was originally appointed Lancaster Herald by Charles I but then sided with Cromwell, did not even have a tabard with the Royal Arms, as his own had been "plundered in the wars". He had to borrow a decorative one from the tomb of James I in

On 8 May 1660, the heralds at the command of the Convention Parliament proclaimed Charles II, King at Westminster Hall Gate. It was said that William Ryley, who was originally appointed Lancaster Herald by Charles I but then sided with Cromwell, did not even have a tabard with the Royal Arms, as his own had been "plundered in the wars". He had to borrow a decorative one from the tomb of James I in  By 1683 the College part of the structure was finished. The new building was built out of plain bricks of three storeys, with basement and attic levels in addition. The College consists of an extensive range of quadrangular buildings. Apart from the hall, a porter's lodge and a public office, the rest of the building was given over to the heralds as accommodation. To the east and south sides three

By 1683 the College part of the structure was finished. The new building was built out of plain bricks of three storeys, with basement and attic levels in addition. The College consists of an extensive range of quadrangular buildings. Apart from the hall, a porter's lodge and a public office, the rest of the building was given over to the heralds as accommodation. To the east and south sides three

The

The  Great financial strains placed upon the College during these times were relieved when the extravagant Prince Regent (the future

Great financial strains placed upon the College during these times were relieved when the extravagant Prince Regent (the future

On 18 October 1869, a warrant for a commission of inquiry into the state of the College was established. The warrant issued on the behalf of the

On 18 October 1869, a warrant for a commission of inquiry into the state of the College was established. The warrant issued on the behalf of the  Despite the findings of this inquiry, the issues surrounding the status and position of the College continued. At the beginning of the 20th century these issues were once again brought to the forefront. In 1903 an inquiry was set up at the instructions of

Despite the findings of this inquiry, the issues surrounding the status and position of the College continued. At the beginning of the 20th century these issues were once again brought to the forefront. In 1903 an inquiry was set up at the instructions of

In 1934, on the 450th anniversary of the incorporation of the College of Arms, an exhibition was held at the College of the heralds' principal treasures and other associated interests. The exhibition was opened by the

In 1934, on the 450th anniversary of the incorporation of the College of Arms, an exhibition was held at the College of the heralds' principal treasures and other associated interests. The exhibition was opened by the  In the year of the quincentenary of the incorporation of the College of Arms, the College held a special service of thanksgiving at

In the year of the quincentenary of the incorporation of the College of Arms, the College held a special service of thanksgiving at

The College of Arms is a part of the Royal Household of the

The College of Arms is a part of the Royal Household of the  The participation of these two annual ceremonies are considered the least time-consuming part of the herald's roles. However at other times they are involved in some of the most important ceremonies concerning the life of the British monarch. After the death of a Sovereign the

The participation of these two annual ceremonies are considered the least time-consuming part of the herald's roles. However at other times they are involved in some of the most important ceremonies concerning the life of the British monarch. After the death of a Sovereign the  At

At

The granting of

The granting of  In the past this issue of eligibility has been a source of great conflict between the heralds; such submissions are made on an officer for clients basis, which meant some 'unsuitability' was ignored in lieu of profit by past officers. Suitability rested on the phrase "eminent men", originally the test applied was one of wealth or social status, as any man entitled to bear a coat of arms was expected to be a

In the past this issue of eligibility has been a source of great conflict between the heralds; such submissions are made on an officer for clients basis, which meant some 'unsuitability' was ignored in lieu of profit by past officers. Suitability rested on the phrase "eminent men", originally the test applied was one of wealth or social status, as any man entitled to bear a coat of arms was expected to be a  As soon as the composition of the

As soon as the composition of the

Due to the inheritable nature of coats of arms the College have also been involved in

Due to the inheritable nature of coats of arms the College have also been involved in

The most recognisable item of the herald's wardrobe has always been their tabards. Since the 13th century, records of this distinctive garment were apparent. At first it is likely that the herald wore his master's cast-off coat, but even from the beginning that would have had special significance, signifying that he was in effect his master's representative. Especially when his master was a sovereign prince, the wearing of his coat would haven given the herald a natural diplomatic status. John Anstis wrote that: "The Wearing the outward Robes of the Prince, hath been esteemed by the Consent of Nations, to be an extraordinary Instance of Favour and Honour, as in the Precedent of ''Mordecai'', under a king of Persia." The last King of England to have worn a tabard with his arms was probably King Henry VII. Today the herald's tabard is a survivor of history, much like the Court dress#Judges, judges' wigs and (until the last century) the bishop's gaiters.

The most recognisable item of the herald's wardrobe has always been their tabards. Since the 13th century, records of this distinctive garment were apparent. At first it is likely that the herald wore his master's cast-off coat, but even from the beginning that would have had special significance, signifying that he was in effect his master's representative. Especially when his master was a sovereign prince, the wearing of his coat would haven given the herald a natural diplomatic status. John Anstis wrote that: "The Wearing the outward Robes of the Prince, hath been esteemed by the Consent of Nations, to be an extraordinary Instance of Favour and Honour, as in the Precedent of ''Mordecai'', under a king of Persia." The last King of England to have worn a tabard with his arms was probably King Henry VII. Today the herald's tabard is a survivor of history, much like the Court dress#Judges, judges' wigs and (until the last century) the bishop's gaiters.

The tabards of the different officers can be distinguished by the type of fabric used to make them. A tabard of a King of Arms is made of velvet and cloth of gold, the tabard of a Herald of satin and that of a Pursuivant of damask silk. The tabards of all heralds (Ordinary and Extraordinary) are inscribed with the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, Sovereign's royal arms, richly embroidered. It was once the custom for pursuivants to wear their tabards with the sleeves at the front and back, in fact in 1576 a pursuivant was fined for presuming to wear his tabard like a herald but this practice was ended during the reign of James II. Until 1888 all tabards was provided to the heralds by the Crown, however in that year a parsimonious Treasury refused to ask Parliament of the United Kingdom, Parliament for funds for the purpose. Ever since then heralds either paid for their own tabards or bought the one used by their predecessors. The newest tabard was made in 1963 for the Welsh Herald Extraordinary. A stock of them is now held by the Lord Chamberlain, from which a loan "during tenure of office" is made upon each appointment. They are often sent to Ede & Ravenscroft for repair or replacement. In addition, heralds and pursuivants wear black velvet caps with a badge embroidered.

The tabards of the different officers can be distinguished by the type of fabric used to make them. A tabard of a King of Arms is made of velvet and cloth of gold, the tabard of a Herald of satin and that of a Pursuivant of damask silk. The tabards of all heralds (Ordinary and Extraordinary) are inscribed with the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, Sovereign's royal arms, richly embroidered. It was once the custom for pursuivants to wear their tabards with the sleeves at the front and back, in fact in 1576 a pursuivant was fined for presuming to wear his tabard like a herald but this practice was ended during the reign of James II. Until 1888 all tabards was provided to the heralds by the Crown, however in that year a parsimonious Treasury refused to ask Parliament of the United Kingdom, Parliament for funds for the purpose. Ever since then heralds either paid for their own tabards or bought the one used by their predecessors. The newest tabard was made in 1963 for the Welsh Herald Extraordinary. A stock of them is now held by the Lord Chamberlain, from which a loan "during tenure of office" is made upon each appointment. They are often sent to Ede & Ravenscroft for repair or replacement. In addition, heralds and pursuivants wear black velvet caps with a badge embroidered.

Apart from the tabards, the heralds also wear scarlet Court uniform and dress in the United Kingdom, court uniforms with gold embroidery during formal events; with white breeches and stockings for coronations and black for all other times together with black patent court shoes with gold buckles (the Scottish heralds wear black wool serge military style trousers with wide gold oak leaf lace on the side seams and black patent ankle boots; or for women, a long black skirt). The heralds are also entitled to distinctive sceptres, which have been a symbol of their office since the Tudor period. In 1906 new sceptres were made, most likely the initiative of Alfred Scott-Gatty, Sir Alfred Scott-Gatty. These take the form of short black Baton (symbol), batons with gilded ends, each with a representation of the badges of the different offices of the heralds. In 1953 these were replaced by white staves, with gilded metal handles and at its head a blue dove in a golden coronet or a "martinet". These blue martinets are derived from the arms of the College. Another of the heralds' insignia of office is the Livery collar, Collar of SS, which they wear over their uniforms. During inclement weather, a large black cape is worn. At state funerals, they would wear a wide sash of black silk sarsenet over their tabards (in ancient times, they would have worn long black hooded cloaks under their tabards).

The three Kings of Arms have also been entitled to wear a Crown (headgear), crown since the 13th century. However, it was not until much later that the specific design of the crown was regulated. The silver-gilt crown is composed of sixteen acanthus leaves alternating in height, inscribed with a line from Psalm 51 in Latin: ''Miserere mei Deus secundum magnam misericordiam tuam'' (translated: Have mercy on me O God according to Thy great mercy). Within the crown is a cap of crimson velvet, lined with Stoat, ermine, having at the top a large tuft of tassels, wrought in gold. In medieval times the king of arms were required to wear their crowns and attend to the Sovereign on four high feasts of the year: Christmas, Easter, Whitsuntide and All Saint's Day. Today, the crown is reserved for the most solemn of occasions. The last time these crowns were worn was at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. At other times, kings of arms wear a black bicorne trimmed with white ostrich feathers when performing duties outdoors, or a black velvet cap, depending on circumstances of occasion.

The New Zealand Herald of Arms Extraordinary is a special case when it comes to uniform. Although they do wear the tabard, they only do so when in the UK performing duties. When in New Zealand, they simply wear morning dress as official uniform, together with their chains and baton.

Apart from the tabards, the heralds also wear scarlet Court uniform and dress in the United Kingdom, court uniforms with gold embroidery during formal events; with white breeches and stockings for coronations and black for all other times together with black patent court shoes with gold buckles (the Scottish heralds wear black wool serge military style trousers with wide gold oak leaf lace on the side seams and black patent ankle boots; or for women, a long black skirt). The heralds are also entitled to distinctive sceptres, which have been a symbol of their office since the Tudor period. In 1906 new sceptres were made, most likely the initiative of Alfred Scott-Gatty, Sir Alfred Scott-Gatty. These take the form of short black Baton (symbol), batons with gilded ends, each with a representation of the badges of the different offices of the heralds. In 1953 these were replaced by white staves, with gilded metal handles and at its head a blue dove in a golden coronet or a "martinet". These blue martinets are derived from the arms of the College. Another of the heralds' insignia of office is the Livery collar, Collar of SS, which they wear over their uniforms. During inclement weather, a large black cape is worn. At state funerals, they would wear a wide sash of black silk sarsenet over their tabards (in ancient times, they would have worn long black hooded cloaks under their tabards).

The three Kings of Arms have also been entitled to wear a Crown (headgear), crown since the 13th century. However, it was not until much later that the specific design of the crown was regulated. The silver-gilt crown is composed of sixteen acanthus leaves alternating in height, inscribed with a line from Psalm 51 in Latin: ''Miserere mei Deus secundum magnam misericordiam tuam'' (translated: Have mercy on me O God according to Thy great mercy). Within the crown is a cap of crimson velvet, lined with Stoat, ermine, having at the top a large tuft of tassels, wrought in gold. In medieval times the king of arms were required to wear their crowns and attend to the Sovereign on four high feasts of the year: Christmas, Easter, Whitsuntide and All Saint's Day. Today, the crown is reserved for the most solemn of occasions. The last time these crowns were worn was at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. At other times, kings of arms wear a black bicorne trimmed with white ostrich feathers when performing duties outdoors, or a black velvet cap, depending on circumstances of occasion.

The New Zealand Herald of Arms Extraordinary is a special case when it comes to uniform. Although they do wear the tabard, they only do so when in the UK performing duties. When in New Zealand, they simply wear morning dress as official uniform, together with their chains and baton.

There are no formal qualifications for a herald, but certain specialist knowledge and discipline are required. Most of the current officers are trained lawyers and historians. Noted heraldist and writer John Ferne, Sir John Ferne wrote in ''The Glory of Generositie'' in 1586 that a herald "ought to be a Gentlemen and an Old man not admitting into that sacred office everie glasier, painter & tricker, or a meere blazonner of Armes: for to the office of a herald is requisite the skill of many faculties and professions of literature, and likewise the knowledge of warres." Some of the greatest scholars and eminent antiquarians of their age were members of the College, such as Robert Glover (officer of arms), Robert Glover, William Camden, William Dugdale, Sir William Dugdale, Elias Ashmole, John Anstis,

There are no formal qualifications for a herald, but certain specialist knowledge and discipline are required. Most of the current officers are trained lawyers and historians. Noted heraldist and writer John Ferne, Sir John Ferne wrote in ''The Glory of Generositie'' in 1586 that a herald "ought to be a Gentlemen and an Old man not admitting into that sacred office everie glasier, painter & tricker, or a meere blazonner of Armes: for to the office of a herald is requisite the skill of many faculties and professions of literature, and likewise the knowledge of warres." Some of the greatest scholars and eminent antiquarians of their age were members of the College, such as Robert Glover (officer of arms), Robert Glover, William Camden, William Dugdale, Sir William Dugdale, Elias Ashmole, John Anstis,

College of Arms Trust

The National Archives' page for the College of Arms

The White Lion Society

The Heraldry Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:College Of Arms College of Arms, 1484 establishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1683 Former houses in the City of London Government agencies established in 1484 Grade I listed buildings in the City of London Heraldic authorities Organisations based in the City of London

corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and r ...

consisting of professional officers of arms

An officer of arms is a person appointed by a sovereign or state with authority to perform one or more of the following functions:

* to control and initiate armorial matters;

* to arrange and participate in ceremonies of state;

* to conserve an ...

, with jurisdiction over England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

and some Commonwealth realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state in the Commonwealth of Nations whose monarch and head of state is shared among the other realms. Each realm functions as an independent state, equal with the other realms and nations of the Commonwealt ...

s. The heralds are appointed by the British Sovereign

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

and are delegated authority to act on behalf of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

in all matters of heraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branch ...

, the granting of new coats of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its wh ...

, genealogical research and the recording of pedigrees. The College is also the official body responsible for matters relating to the flying of flags on land, and it maintains the official registers of flags and other national symbols. Though a part of the Royal Household of the United Kingdom

The Royal Households of the United Kingdom are the collective departments that support members of the British royal family. Many members of the royal family who undertake public duties have separate households. They vary considerably in size, ...

, the College is self-financed, unsupported by any public funds.

Founded by royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

in 1484 by King Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

, the College is one of the few remaining official heraldic authorities

A heraldic authority is defined as an office or institution which has been established by a reigning monarch or a government to deal with heraldry in the country concerned. It does not include private societies or enterprises which design and/or r ...

in Europe. Within the United Kingdom, there are two such authorities, the Court of the Lord Lyon

The Court of the Lord Lyon (the Lyon Court) is a standing court of law, based in New Register House in Edinburgh, which regulates heraldry in Scotland. The Lyon Court maintains the register of grants of arms, known as the Public Register of All A ...

in Scotland and the College of Arms for the rest of the United Kingdom. The College has had its home in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

since its foundation, and has been at its present location, on Queen Victoria Street, since 1555. The College of Arms also undertakes and consults on the planning of many ceremonial occasions such as coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

s, state funerals, the annual Garter Service

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

and the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

. Heralds of the College accompany the sovereign on many of these occasions.

The College comprises thirteen officers or heralds: three Kings of Arms

King of Arms is the senior rank of an officer of arms. In many heraldic traditions, only a king of arms has the authority to grant armorial bearings and sometimes certify genealogies and noble titles. In other traditions, the power has been de ...

, six Heralds of Arms and four Pursuivants of Arms. There are also seven officers extraordinary, who take part in ceremonial occasions but are not part of the College. The entire corporation is overseen by the Earl Marshal

Earl marshal (alternatively marschal or marischal) is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England (then, following the Act of Union 1800, in the United Kingdom). He is the eig ...

, a hereditary office always held by the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

.

History

Foundation

King

King Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

's interest in heraldry was indicated by his possession of two important rolls of arms

Roll or Rolls may refer to:

Movement about the longitudinal axis

* Roll angle (or roll rotation), one of the 3 angular degrees of freedom of any stiff body (for example a vehicle), describing motion about the longitudinal axis

** Roll (aviation), ...

. While still Duke of Gloucester

Duke of Gloucester () is a British royal title (after Gloucester), often conferred on one of the sons of the reigning monarch. The first four creations were in the Peerage of England and the last in the Peerage of the United Kingdom; the curren ...

and Constable of England

The Lord High Constable of England is the seventh of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Great Chamberlain and above the Earl Marshal. This office is now called out of abeyance only for coronations. The Lord High Constable w ...

for his brother (Edward IV

Edward IV (28 April 1442 – 9 April 1483) was King of England from 4 March 1461 to 3 October 1470, then again from 11 April 1471 until his death in 1483. He was a central figure in the Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars in England ...

) from 1469, he in the latter capacity supervised the heralds and made plans for the reform of their organisation. Soon after his accession to the throne he created Sir John Howard as Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

and Earl Marshal of England

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant "chieftain", particular ...

, who became the first Howard

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

appointed to both positions.

In the first year of his reign, the royal heralds were incorporated under royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

dated 2 March 1484, under the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

name "''Le Garter regis armorum Anglicorum, regis armorum partium Australium, regis armorum partium Borealium, regis armorum Wallæ et heraldorum, prosecutorum, sive pursevandorum armorum.''" Translated as: "the Garter King of Arms of England, the King of Arms of the Southern parts, the King of Arms of the Northern parts, the King of Arms of Wales, and all other heralds and pursuivants of arms". (translated by author from Latin) The charter then goes on to state that the heralds "for the time being, shall be in perpetuity a body corporate in fact and name, and shall preserve a succession unbroken." This charter titled "''Literæ de incorporatione heraldorum''" is now held in the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

.

There has been some evidence that prior to this charter, the royal heralds had already in some ways behaved like a corporation as early as 1420. Nevertheless, the charter is the earliest surviving document to affirm the chapter as a corporate body

A juridical person is a non-human legal person that is not a single natural person but an organization recognized by law as a fictitious person such as a corporation, government agency, NGO or International (inter-governmental) Organization (suc ...

of heralds. The charter outlines the constitution of the officers, their hierarchy, the privileges conferred upon them and their jurisdiction over all heraldic matters in the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

.

The King empowered the College to have and use only one common seal of authority, and also instructed them to find a chaplain to celebrate mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

daily for himself, Anne Neville

Anne Neville (11 June 1456 – 16 March 1485) was Queen of England as the wife of King Richard III. She was the younger of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (the "Kingmaker"). Before her marriage to Ric ...

, the Queen Consort, and his heir, Prince Edward. The College was also granted a house named Coldharbour (formerly Poulteney's Inn) on Upper Thames Street

Thames Street, divided into Lower and Upper Thames Street, is a road in the City of London, the historic and financial centre of London. It forms part of the busy A3211 route (prior to being rebuilt as a major thoroughfare in the late 1960s, it ...

in the parish of All-Hallows-the-Less

All-Hallows-the-Less (also known as ''All-Hallows-upon-the-Cellar'') was a church in the City of London. Of medieval origin, it was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and not rebuilt.

History

The church stood on the south side of Tham ...

, for storing records and living space for the heralds. The house, built by Sir John de Pulteney

Sir John de Pulteney (sometimes spelled Poultney; died 8 June 1349) was a major English entrepreneur and property owner, who served four times as Mayor of London.

Background

A biography of Sir John, written by Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, tha ...

, four times Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional powe ...

, was said to be one of the greatest in the City of London.

Varying fortunes

The defeat and death of Richard III at Bosworth field was a double blow for the heralds, for they lost both their patron, the King, and their benefactor, the Earl Marshal, who was also slain. The victorious Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII soon after the battle. Henry's first Parliament of 1485 passed an Act of Resumption, in which large grants of crown properties made by his two predecessors to their supporters were cancelled. Whether this act affected the status of the College's charter is debatable; however, the act did facilitate the de facto recovery of Coldharbour to the crown. Henry then granted the house to his mother

The defeat and death of Richard III at Bosworth field was a double blow for the heralds, for they lost both their patron, the King, and their benefactor, the Earl Marshal, who was also slain. The victorious Henry Tudor was crowned King Henry VII soon after the battle. Henry's first Parliament of 1485 passed an Act of Resumption, in which large grants of crown properties made by his two predecessors to their supporters were cancelled. Whether this act affected the status of the College's charter is debatable; however, the act did facilitate the de facto recovery of Coldharbour to the crown. Henry then granted the house to his mother Lady Margaret Beaufort

Lady Margaret Beaufort (usually pronounced: or ; 31 May 1441/43 – 29 June 1509) was a major figure in the Wars of the Roses of the late fifteenth century, and mother of King Henry VII of England, the first Tudor monarch.

A descendant of ...

, for life. This was because it was supposed that the house was granted personally to John Writhe

John Writhe (died 1504) was a long-serving English officer of arms. He was probably the son of William Writhe, who represented the borough of Cricklade in the Parliament of 1450–51, and is most remembered for being the first Garter King of Arms ...

the Garter King of Arms and not to the heralds as a corporation. As a result, the heralds were left destitute and many of their books and records were lost. Despite this ill treatment from the King, the heralds' position at the royal court

A royal court, often called simply a court when the royal context is clear, is an extended royal household in a monarchy, including all those who regularly attend on a monarch, or another central figure. Hence, the word "court" may also be appl ...

remained, and they were compelled by the King to attend him at all times (albeit in rotation).

Of the reign of King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, it has been said that: "at no time since its establishment, was he college

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

in higher estimation, nor in fuller employment, than in this reign." Henry VIII was fond of pomp and magnificence, and thus gave the heralds plenty of opportunity to exercise their roles in his court. In addition, the members of the College were also expected to be regularly despatched to foreign courts on missions, whether to declare war, accompany armies, summon garrisons or deliver messages to foreign potentates and generals. During his magnificent meeting with Francis I of France

Francis I (french: François Ier; frm, Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once ...

at the Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold (french: Camp du Drap d'Or, ) was a summit meeting between King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France from 7 to 24 June 1520. Held at Balinghem, between Ardres in France and Guînes in the English P ...

in 1520, Henry VIII brought with him eighteen officers of arms, probably all he had, to regulate the many tournaments and ceremonies held there.

Nevertheless, the College's petitions to the King and to the

Nevertheless, the College's petitions to the King and to the Duke of Suffolk

Duke of Suffolk is a title that has been created three times in the peerage of England.

The dukedom was first created for William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, William de la Pole, who had already been elevated to the ranks of earl and marquess ...

in 1524 and 1533 for the return of their chapter house were rejected, and the heralds were left to hold chapter in whichever palace the royal court happened to be at the time. They even resorted to meeting at each other's houses, at various guildhalls and even a hospital. Furthermore, Henry VIII's habit of raising ladies in the situation of subjects to queens, and then awarding them many heraldic augmentations, which also extended to their respective families, was considered harmful to the science of heraldry. The noted antiquarian and heraldist Charles Boutell

Charles Boutell (1 August 1812 – 31 July 1877) was an English archaeologist, antiquary and clergyman, publishing books on brasses, arms and armour and heraldry, often illustrated by his own drawings.

Life

Boutell was born at Pulham St Mary, N ...

commented in 1863, that the: "Arms of Queen Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

are the first which exemplify the usage, introduced by Henry VIII, of granting to his Consorts 'Augmentations' to their paternal arms. It is a striking illustration of the degenerate condition of Heraldry under the second Tudor Sovereign."

It was also in this reign in 1530, that Henry VIII conferred on the College one of its most important duties for almost a century, the heraldic visitation

Heraldic visitations were tours of inspection undertaken by Kings of Arms (or alternatively by heralds, or junior officers of arms, acting as their deputies) throughout England, Wales and Ireland. Their purpose was to register and regulate the ...

. The provincial Kings of Arms were commissioned under a royal warrant to enter all houses and churches and given authority to deface and destroy all arms unlawfully used by any knight, esquire, or gentleman. Around the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries this duty became even more necessary as the monasteries were previously repositories of local genealogical records. From then on, all genealogical records and the duty of recording them was subsumed by the College. These visitations were serious affairs, and many individuals were charged and heavily fined for breaking the law of arms

The law of heraldic arms (or laws of heraldry) governs the "bearing of arms", that is, the possession, use or display of arms, also called coats of arms, coat armour or armorial bearings. Although it is believed that the original function of coat ...

. Hundreds of these visitations were carried out well into the 17th century; the last was in 1686.

Reincorporation

The College found a patroness in

The College found a patroness in Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

, although it must have been embarrassing for both sides, after the heralds initially proclaimed the right of her rival Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

to the throne. When King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

died on 6 July 1553, Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen four days later, first in Cheapside

Cheapside is a street in the City of London, the historic and modern financial centre of London, which forms part of the A40 London to Fishguard road. It links St. Martin's Le Grand with Poultry. Near its eastern end at Bank junction, where ...

then in Fleet Street

Fleet Street is a major street mostly in the City of London. It runs west to east from Temple Bar at the boundary with the City of Westminster to Ludgate Circus at the site of the London Wall and the River Fleet from which the street was na ...

by two heralds, trumpets blowing before them. However, when popular support swung to Mary's side, the Lord Mayor of London and his councils accompanied by the Garter King of Arms, two other heralds, and four trumpeters returned to Cheapside to proclaim Mary's ascension as rightful queen instead. The College's excuse was that they were compelled in their earlier act by the Duke of Northumberland

Duke of Northumberland is a noble title that has been created three times in English and British history, twice in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of Great Britain. The current holder of this title is Ralph Percy, 12th Duke ...

(Lady Jane's father-in-law, who was later executed), an excuse that Mary accepted.

The queen and her husband (and co-sovereign) Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

then set about granting the College a new house called Derby Place or Derby House, under a new charter, dated 18 July 1555 at Hampton Court Palace

Hampton Court Palace is a Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the chie ...

. The house was built by Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby

Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby, KG (1435 – 29 July 1504) was an English nobleman. He was the stepfather of King Henry VII of England. He was the eldest son of Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley and Joan Goushill.

A landed magnate of imm ...

, who married Lady Margaret Beaufort in 1482 and was created the 1st Earl of Derby

Earl of Derby ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. The title was first adopted by Robert de Ferrers, 1st Earl of Derby, under a creation of 1139. It continued with the Ferrers family until the 6th Earl forfeited his property toward the end ...

in 1485. The house was built in 1503 and was given to the Crown by the 3rd Earl in 1552/3 in exchange for some land. The charter stated that the house would: "enable them he College

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

to assemble together, and consult, and agree amongst themselves, for the good of their faculty, and that the records and rolls might be more safely and conveniently deposited." The charter also reincorporated the three kings of arms, six heralds and all other heralds and pursuivants, and their successors, into a corporation with perpetual succession. A new seal of authority, with the College's full coat of arms was also engraved. On 16 May 1565, the name "the House of the Office of Arms" was used, thereafter in May 1566 "our Colledge of Armes", and in January 1567 "our House of the College of the office of arms".

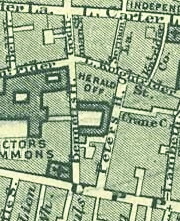

Derby Place was situated in the parish of St Benedict and St Peter, south of St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

, more or less on the College's present location. There are records of the heralds carrying out modifications to the structure of Derby Place over many years. However, little record of its appearance has survived, except the description that the buildings formed three sides of a quadrangle, entered through a gate with a portcullis on the west side. On the south range, roughly where Queen Victoria Street now stands, was a large hall on the western end. Derby Place's hearth tax

A hearth tax was a property tax in certain countries during the medieval and early modern period, levied on each hearth, thus by proxy on wealth. It was calculated based on the number of hearths, or fireplaces, within a municipal area and is cons ...

bill from 1663, discovered in 2009 at the National Archives at Kew

Kew () is a district in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. Its population at the 2011 census was 11,436. Kew is the location of the Royal Botanic Gardens ("Kew Gardens"), now a World Heritage Site, which includes Kew Palace. Kew is a ...

, showed that the building had about thirty-two rooms, which were the workplace as well as the home to eleven officers of arms.

The reign of Mary's sister

The reign of Mary's sister Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

saw the College's privileges confirmed by an Act of Parliament in 1566. As well as the drawing up of many important internal statutes and ordinances for the College by Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, the Earl Marshal, dated 18 July 1568. The long reign saw the College distracted by the many quarrels between Garter William Dethick, Clarenceux Robert Cooke and York Herald Ralph Brooke about their rights and annulments. Disputes in which the other officers also took part, often occurred among the lesser heralds against each other. Historian Mark Noble

Mark James Noble (born 8 May 1987) is an English former professional footballer who played as a central midfielder and is well remembered for his time at English club West Ham United, spending eighteen years with the club. Apart from two sh ...

wrote in 1805, that these fights often involved the use of "every epithet that was disgraceful to themselves and their opponents." and that "Their accusations against each other would fill a volume." During these years, the College's reputation was greatly injured in the eyes of the public.

The reason behind these discords were laid on the imperfect execution of the reorganisation of the College in 1568 and the uncertainty over issue of granting arms to the new and emerging gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

of the era. An enquiry into the state of the College lasted for one year, finally reporting to William Cecil, Baron Burghley in 1596; as a consequence, many important measures of reform for the College were made in the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

. Eventually, these animosities among the heralds in the College ended only after the expulsion of one and the death of another.

Civil War

When theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

began in 1642 during the reign of King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, the College was divided: three kings of arms, three heralds and one pursuivant sided with the King and the Royalists

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

, while the other officers began to court the services of the Parliamentarian side. Nevertheless, the heralds petitioned Parliament in the same year, to protect their: "Books of Record, Registers, Entries, Precedents, Arms, Pedigrees and Dignities." In 1643 the heralds joined the King at Oxford, and were with him at Naseby

Naseby is a village in West Northamptonshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 Census was 687.

The village is 14 mi (22.5 km) north of Northampton, 13.3 mi (21.4 km) northeast of Daventry, and 7&nb ...

and followed him on all of his campaigns. Sir Edward Walker

Sir Edward Walker (1611 – February 1677) was an officer of arms and antiquarian who served as Garter King of Arms.

Early life

Walker was born in 1611 at Roobers in Nether Stowey, Somerset, and entered the household of the great Earl Marshal ...

the Garter King of Arms (from 1645) was even appointed, with the permission of Parliament, to act as the King's chief secretary at the negotiations at Newport. After the execution of Charles I, Walker joined Charles II in his exile in the Netherlands.

Meanwhile, on 3 August 1646 the Committee of Sequestration took possession of the College premises, and kept it under its own authority. Later in October, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

ordered the committee to directly remove those officers whose loyalties were with the King and to nominate their own candidates to fill these vacant offices. Those officers whose loyalty remained with the King were persecuted; first they were deprived of their offices, then of their emoluments, then a fine was imposed and some were even imprisoned. In spite of this, the institutional College was protected by the Parliamentarians, and their rights and work continued unabated. Edward Bysshe

Sir Edward Bysshe FRS (1615?–1679) was an English barrister, politician and officer of arms. He sat in the House of Commons variously between 1640 and 1679 and was Garter King of Arms during the Commonwealth period.

Life

Bysshe was born at S ...

a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

from Bletchingley

Bletchingley (historically "Blechingley") is a village in Surrey, England. It is on the A25 road to the east of Redhill, Surrey, Redhill and to the west of Godstone, has a conservation area with Middle Ages, medieval buildings and is mostly on a ...

was appointed Garter, thus "Parliament which rejected its King created for itself a King of Arms". During this time the heralds continued their work and were even present on 26 June 1657 at Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

's second installation ceremony as Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

.

Survival

On 8 May 1660, the heralds at the command of the Convention Parliament proclaimed Charles II, King at Westminster Hall Gate. It was said that William Ryley, who was originally appointed Lancaster Herald by Charles I but then sided with Cromwell, did not even have a tabard with the Royal Arms, as his own had been "plundered in the wars". He had to borrow a decorative one from the tomb of James I in

On 8 May 1660, the heralds at the command of the Convention Parliament proclaimed Charles II, King at Westminster Hall Gate. It was said that William Ryley, who was originally appointed Lancaster Herald by Charles I but then sided with Cromwell, did not even have a tabard with the Royal Arms, as his own had been "plundered in the wars". He had to borrow a decorative one from the tomb of James I in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

instead; the garment was duly returned the next day. The Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of Charles II annulled all the Acts of the Parliament and all the actions of the Lord Protector, without penalising any of their supporters (except for the regicides). Accordingly, all the grant of arms of the Commonwealth College was declared null and void. Furthermore, all heralds appointed during the Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

lost their offices, while those appointed originally by Charles I returned to their places. The exception was Edward Bysshe, who was removed as Garter, but was instead appointed Clarenceux in 1661, much to the chagrin of Garter Edward Walker.

In 1666 as the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

swept through the city, Derby Place, the College's home since 1555, was completely gutted and destroyed. Fortunately the College's library was saved, and at first was stored in the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. H ...

, then later moved to the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, where a temporary office was opened in an apartment called the Queen's court. An announcement was also made in the ''London Gazette

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

'' to draw public notice to the situation. Due to a shortage of funds, the planned rebuilding of a new College was delayed until 1670. It was then that Francis Sandford, the Rouge Dragon Pursuivant and Morris Emmett, the King's bricklayer, were together able to design and begin construction of a new structure on the old site. The costs of the rebuilding was financed in stages, and the structure was erected slowly in parts. The heralds contributed significantly out of their own pockets; at the same time, they also sought subscriptions among the nobility, with the names of contributors recorded into a series of splendid manuscripts known as the Benefactors Books.

By 1683 the College part of the structure was finished. The new building was built out of plain bricks of three storeys, with basement and attic levels in addition. The College consists of an extensive range of quadrangular buildings. Apart from the hall, a porter's lodge and a public office, the rest of the building was given over to the heralds as accommodation. To the east and south sides three

By 1683 the College part of the structure was finished. The new building was built out of plain bricks of three storeys, with basement and attic levels in addition. The College consists of an extensive range of quadrangular buildings. Apart from the hall, a porter's lodge and a public office, the rest of the building was given over to the heralds as accommodation. To the east and south sides three terraced house

In architecture and city planning, a terrace or terraced house ( UK) or townhouse ( US) is a form of medium-density housing that originated in Europe in the 16th century, whereby a row of attached dwellings share side walls. In the United State ...

s were constructed for leases, their façade in keeping with the original design. In 1699 the hall, which for some time had been used as a library, was transformed into the Earl Marshal's Court or the Court of Chivalry; it remains so to this day. In 1776 some stylistic changes were made to the exterior of the building and some details, such as pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedimen ...

s and cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, around the top edge of a ...

s were removed, transforming the building to the then popular but austere Neo-Classical style

Neoclassical architecture is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy and France. It became one of the most prominent architectural styles in the Western world. The prevailing style ...

.

The magnificent coronation of James II in 1685 saw the College revived as an institution of state and the monarchy. However, the abrupt end of his reign saw all but one of the heralds taking the side of William of Orange and Mary II

Mary II (30 April 166228 December 1694) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, co-reigning with her husband, William III & II, from 1689 until her death in 1694.

Mary was the eldest daughter of James, Duke of York, and his first wife ...

in the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

. The period from 1704 to 1706 saw not a single grant of arms being made by the College; this nadir was attributed to the changes in attitude of the times. The Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

between England and Scotland, in the reign of Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

did not affect the jurisdiction or the rights of the College. The College of Arms and the Court of the Lord Lyon

The Court of the Lord Lyon (the Lyon Court) is a standing court of law, based in New Register House in Edinburgh, which regulates heraldry in Scotland. The Lyon Court maintains the register of grants of arms, known as the Public Register of All A ...

were to exist side by side in their respective realms. However, in the matter of precedence; the Lord Lyon

The Right Honourable the Lord Lyon King of Arms, the head of Lyon Court, is the most junior of the Great Officers of State in Scotland and is the Scottish official with responsibility for regulating heraldry in that country, issuing new grant ...

, when in England, was to take immediate precedence behind Garter King of Arms.

Comfortable decay

The

The Hanoverian succession

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, bec ...

to the throne of Great Britain led to reigns with less ceremony than in any since the incorporation of the heralds. The only notable incident for the college in this period, during the reign of George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgor ...

, happened in 1727 when an impostor called Robert Harman pretended to be a herald. The knave was prosecuted by the College in the county of Suffolk, and was sentenced to be pilloried in several market towns on public market days and afterwards to be imprisoned and pay a fine. This hefty sentence was executed, proving that the rights of the College were still respected. In 1737, during the reign of George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

the College petitioned for another charter, to reaffirm their rights and remuneration; this effort proved unsuccessful. Apart from these events the influence of the College was greatly diminished.

In 1742 a Sugar House was built against the wall of the College. This structure was a fire risk and the cause of great anxiety among the heralds. In 1775 the College Surveyor drew attention to this problem, but to no avail. In February 1800, the College was asked by a Select Committee of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

to report to them the state of public records; again the heralds drew attention to the proximity of the Sugar House. Members of the committee inspected the College premises and reported to the House that the College must either be moved to a new building or secured against the risk of fire. Again nothing was done; in 1812 water seeped through the walls of the College damaging records. The Surveyor traced the leak back to a shed recently erected by Mr. Alderman Smith, owner of the Sugar House, who declared his readiness to do everything he could, but who actually did very little to rectify the situation. After years of negotiation the College, in 1820, bought the Sugar House from Smith for the sum of £1,500.

Great financial strains placed upon the College during these times were relieved when the extravagant Prince Regent (the future

Great financial strains placed upon the College during these times were relieved when the extravagant Prince Regent (the future George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

), granted to the College an annual endowment by Royal Warrant on 29 February 1820. This generous endowment from the crown, the first since 1555, was applied towards the reparation and support of the College. Despite the successes of the purchase of the Sugar House and the royal endowment, the College still looked upon the possibility of moving its location to a more suitable and fashionable place. John Nash was at the same time laying out his plans for a new London, and, in 1822, the College, through the Deputy Earl Marshal, asked the government for a portion of land in the new districts on which to build a house to keep their records. A petition from the College was given to the Lords of the Treasury setting out the herald's reason for the move: "that the local situation of the College is so widely detached from the proper scene of the official duties and occupations of Your Memorialists and from the residences of that class of persons by whom the records in their charge are chiefly and most frequently consulted."

Nash himself was asked by the College to design a new building near fashionable Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson commemo ...

but Nash's elaborate plan proved too costly and ambitious for the College. At the same time the College also asked Robert Abraham to submit to them a second plan for the building. When Nash heard that another architect was approached behind his back he reacted vehemently, and attacked the heralds. The College nevertheless continued with their plans. However they were constantly beset by conflicts between the different officers over the amount needed to build a new building. By 1827 the college still had no coherent plan; the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

ordered the College to drop the matter altogether. By 1842 the heralds were reconciled with their location and once again commissioned Abraham to build a new octagonal-shaped Record Room on the site of the old Sugar House.

In 1861 a proposal was made to construct a road from Blackfriars Blackfriars, derived from Black Friars, a common name for the Dominican Order of friars, may refer to:

England

* Blackfriars, Bristol, a former priory in Bristol

* Blackfriars, Canterbury, a former monastery in Kent

* Blackfriars, Gloucester, a f ...

to the Mansion House; this would have resulted in the complete demolition of the College. However, protests from the heralds resulted in only parts of the south east and south west wings being sliced off, requiring extensive remodelling. The College was now a three-sided building with an open courtyard facing the New Queen Victoria Street laid out in 1866. The terrace, steps and entrance porch were also added around this time.

Reform

On 18 October 1869, a warrant for a commission of inquiry into the state of the College was established. The warrant issued on the behalf of the

On 18 October 1869, a warrant for a commission of inquiry into the state of the College was established. The warrant issued on the behalf of the Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

, stated: "that it is desirable that the College of Arms should be visited, and an inquiry instituted with the view of ascertaining whether the Rules and Orders for the good government of the said College ... are duly obeyed and fulfilled ... and whether by change of circumstances or any other cause, any new Laws, Ordinances or Regulations are necessary to be made ... for the said College." The commission had three members: Lord Edward Fitzalan-Howard (the Deputy Earl Marshal), Sir William Alexander

William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling (c. 1567 in Menstrie, Clackmannanshire12 February 1640) was a Scottish courtier and poet who was involved in the Scottish colonisation of Charles Fort, later Port-Royal, Nova Scotia in 1629 and Long Is ...

(Queen's Counsel) and Edward Bellasis (a Sergeant at Law). Sir Bernard Burke (of the famous Burke's Peerage

Burke's Peerage Limited is a British genealogical publisher founded in 1826, when the Irish genealogist John Burke began releasing books devoted to the ancestry and heraldry of the peerage, baronetage, knightage and landed gentry of Great Br ...

), at the time Ulster King of Arms, gave the commission the advice that the College should: "be made a Government Department, let its Officers receive fixed salaries from Government, and let all its fees be paid into the public exchequer. This arrangement would, I am sure, be self-supporting and would raise at once the character of the Office and the status of the Heralds." Burke's suggestion for reform was the same arrangement that had already been applied to the Lord Lyon Court in Scotland in 1867, and was to be applied to his own office in 1871. However unlike the Lyon Court, which was a court of law

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordanc ...

and part of the Scottish Judiciary

The judiciary of Scotland are the judicial office holders who sit in the courts of Scotland and make decisions in both civil and criminal cases. Judges make sure that cases and verdicts are within the parameters set by Scots law, and they ...

, the College of Arms has always been an independent corporate body overseen by the Earl Marshal. While the Lord Lyon depended on the Government for its reforms and statutes, the College has always been able to carry out changes from within itself. The commission also drew attention to the fees, annulments and library of the College, as well as the general modernisation of the chapter as a whole. When the commission made its report in 1870, it recommended many changes, and these were duly made in another warrant dated 27 April 1871. Burke's recommendation, however, was not implemented.

Despite the findings of this inquiry, the issues surrounding the status and position of the College continued. At the beginning of the 20th century these issues were once again brought to the forefront. In 1903 an inquiry was set up at the instructions of

Despite the findings of this inquiry, the issues surrounding the status and position of the College continued. At the beginning of the 20th century these issues were once again brought to the forefront. In 1903 an inquiry was set up at the instructions of Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

, soon to be Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

. The committee of inquiry was to consist of eight members, Sir Algernon West was made chairman. They were tasked to investigate "the constitution, duties and administration of the Heralds' College". The main issues being the anomalous position of the College, who are theoretically officials of the Royal Household, but actually derive their income from fees paid by private individuals for their services. Some of the members of the committee (a minority) wanted (like Burke thirty-four years earlier) to make officers of the College of Arms into "salaried civil servants of the state". Despite concluding that some form of change was necessary, the inquiry categorically stated that any changes "is at the present time and in present circumstances impracticable." In 1905 the generous endowment from the Crown (as instituted by George IV) was stopped by the Liberal Government of the day as part of its campaign against the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

and the class system

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, incom ...

.

A second inquiry was established in 1928 under the chairmanship of Lord Birkenhead

Earl of Birkenhead was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1922 for the noted lawyer and Conservative politician F. E. Smith, 1st Viscount Birkenhead. He was Solicitor-General in 1915, Attorney-General from 1915 to ...

. The inquiry was called soon after a secret memorandum, written in 1927, was circulated by the Home Office, criticising the constitution and workings of the heralds. The memorandum states that "They have, as will be seen from this memorandum, in many cases attempted to interfere with the exercise by the Secretary of State of his constitutional responsibility for advising the Crown", and that the College had "adopted practices in connection with matters within their jurisdiction which seem highly improper in themselves, and calculated to bring the Royal Prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

into contempt." These accusations concern the actions of certain heralds, who overzealously advocate the cases of their paid clients, even against the opposition of the ministers of the day. Sir Anthony Wagner

Sir Anthony Richard Wagner (6 September 1908 – 5 May 1995) was a long-serving officer of arms at the College of Arms in London. He served as Garter Principal King of Arms before retiring to the post of Clarenceux King of Arms. He was one of ...

writes that "The officers of these departments, no doubt, in the overconfident way of their generation, esteemed the College an anachronistic and anomalous institution overdue for reform or abolition." The memorandum ended by saying that "the College of Arms is a small and highly organised luxury trade, dependent for its living on supplying the demand for a fancy article among the well to do: and like many such trades it has in very many cases to create the demand before it can supply it."